Erlang for IoT

Choosing a non-mainstream technology can seem like a risky decision. When the technology is ideally suited to the task at hand, the decision becomes the start of a competitive advantage.

What is Erlang?

Erlang is a programming language used to build massively scalable soft real-time systems with requirements on high availability. (erlang.org)

Sound good?

Some of it uses are in telecoms, banking, e-commerce, computer telephony and instant messaging. Erlang’s runtime system has built-in support for concurrency, distribution and fault tolerance. (erlang.org)

That’s quite a mouthful!

Let’s pick out some key words which are especially relevant to IoT:

- High availability

- Concurrency

- Fault tolerance

I’ll illustrate their importance by discussing a demo platform for ingesting sensor data.

Demo data ingestion platform

To set the scene somewhat, the demo platform will implement the following features:

-

A proprietary and custom communications protocol, delivered using TCP as a transport mechanism. To keeps things simple, the protocol happens to be rather inefficient by only sending 1 sample of sensor data per TCP message. The protocol is not particularly ambitious either, as it only supports 255 physical devices.

-

New TCP connections are always accepted.

-

In order to save battery life, the physical device is allowed to communicate as quickly as it can. In order to prevent errors, the platform can throttle the rate of communication.

-

The physical device transfers data in raw ADC counts. The platform performs calibration, typically based on coefficient values unique to each sensor.

-

A concept of a digital device is introduced. A digital device exists for every physical device the platform is aware of. Digital devices are isolated from one another. Digital devices are uniquely addressable, queryable and actuatable.

Proprietary communications protocol

The following diagram describes a successful communication session for a physical device with 10 samples of sensor data to send to it’s digital counterpart.

The communication session above comprises of 5 types of message. The physical device and the digital device share a common understanding of each messages’ structure. For example, they both know that the first 8 bits will always represent an integer that can be used to identify the type of message (arbitrarily called message_type). This is the reason for the lack of ambition I mentioned, as an 8 bit integer only has a range of 0 to 255.

The protocol has a strict flow of messages, both the physical device and the digital device are maintaining their own copy of the state of a communication session. For example, which message is next due to be sent or received and by whom.

The following table describes the purpose of each type of message.

| message_type | Purpose |

|---|---|

| 1 | The physical device “announcing” itself to the digital device. The first message to be sent after a connection is made and equivalent to the physical device saying “Hello, I’m device with id X and I have 10 samples of data to send”. |

| 2 | The digital device acknowledging receipt of the physical device’s announce message. |

| 3 | The physical device sends a data message. As with message_type a pre-defined number of bits is used for both an integer timestamp and value (a raw ADC count). The range of these integers dictates the timestamp precision and supported minimum and maximum values. |

| 4 | The digital device acknowledging receipt of the physical device’s data message. The digital device knows to expect 9 more data messages. |

| 5 | After receiving an acknowledgment for the 10th data message, the physical device sends a “terminate” message. The last message to be sent before disconnecting. |

So… Erlang?

Being able to design communications protocols as complex as business requirements necessitate is all well and good. But how does Erlang make them easy to implement?

No programming language can be optimised for all use-cases. In stands to reason that a general purpose programming language is somewhat sub-optimal for all use-cases. Erlang was designed for the telecoms industry, i.e. fast and reliable switching and routing of network traffic.

As such Erlang has some unique optimisations.

Handling binary data

Erlang has first-class language constructs for handling binary data.

Consider a contrived analogy regarding spoken languages. German (or other languages featuring noun genders) has an advantage over English.

Take cutlery as an example. If you have a spoon, fork and knife in front of you and you want to pick one, in English you can only say “I take it”. This is ambiguious, what does “it” refer to?

In German (for reasons unclear to me!) a fork is feminine, a spoon is masculine, and a knife is neutral. Which means you can say “ich nehme sie” (“I take her”), “ich nehme ihn” (“I take him”) and “ich nehme es” (“I take it”) respectively. As there are no other gender conflicting nouns in the cutlery context, the ambiguity is resolved. To achieve this in English we would need to add the noun, “I take the fork” etc.

To handle binary data, Erlang doesn’t need to “add the noun”. An Erlang digital device can receive a stream of 0s and 1s, and without any additional processing, know that 0000000100000000000000010000000000001010 is the physical device with id 1 “announcing” it has 10 samples of data to send.

Fault tolerance

People don’t tend to complain when something just works. Ericsson designed the first version of Erlang in the 1980’s and in a recent news article revealed they still use it today in their network solutions to carry an estimated 40 percent of all mobile traffic worldwide. When it does fail, it makes the national news. This is probably because for the vast majority of the time it works perfectly in the background without failure, or at least without noticeable failure (which is an important distinction).

The late Joe Armstrong (Erlang’s creator) writes that Ericsson’s flagship project (the AXD301 switch) had over 2 million lines of Erlang and achieved a staggering nine nines reliability (99.9999999%!). Erlang features isolated units of execution, known as processes, that communicate via message passing. These processes are incredibly lightweight, with a single server able to run tens of thousands of them. Processes, either singular or in groups, can be monitored by other processes and restarted with varying strategies when failures occurs. Erlang embraces failure as inevitable, and provides tools to recover.

Process design

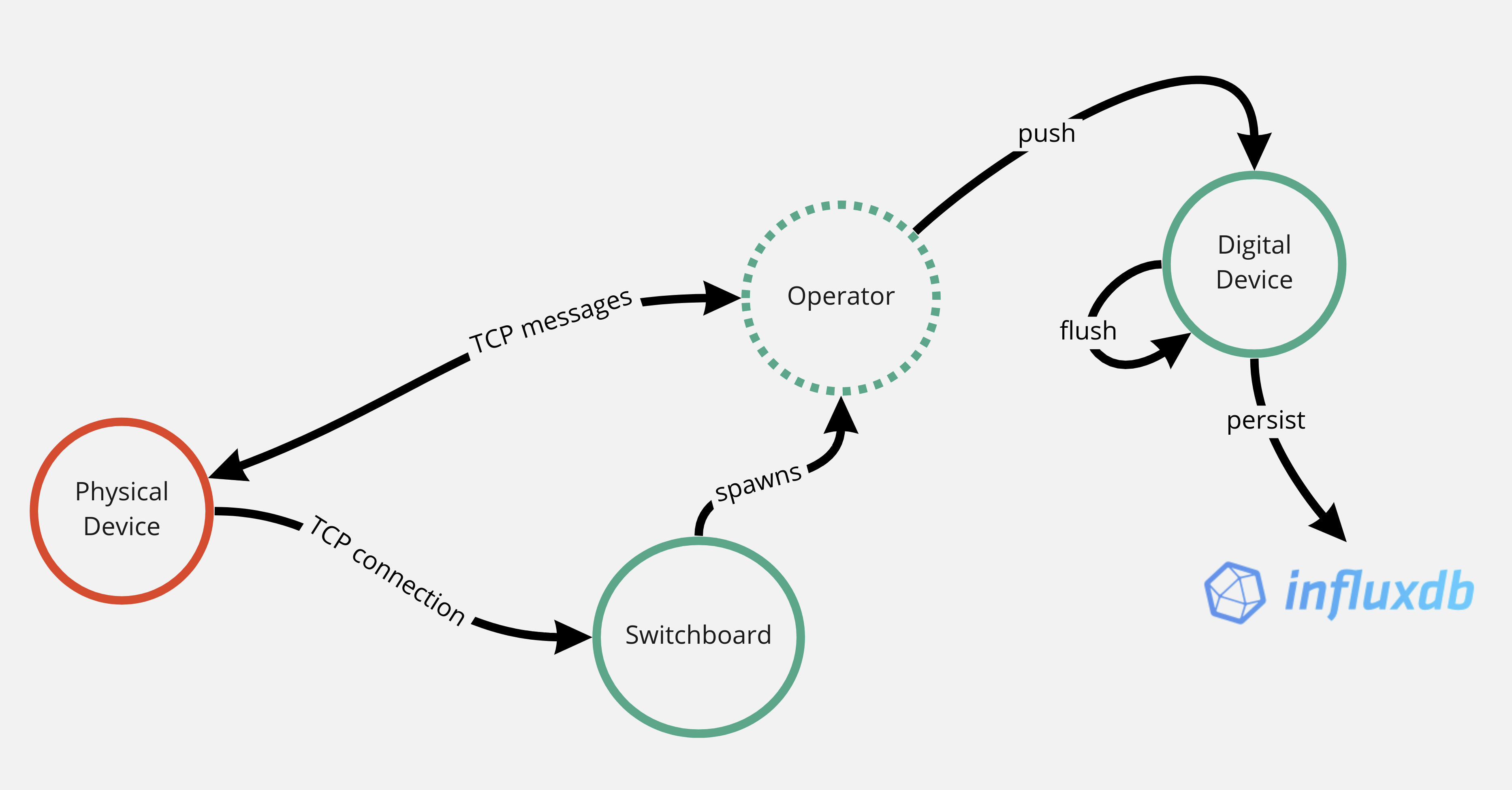

Architecting a system in Erlang is essentially a case of designing how processes and process groups interact, fail and recover. The design options are broad, but at a high level one process per physical device is idiomatic. At a level lower, the following diagram illustrates the process design employed by the demo platform.

A call centre is a perfect analogy of the demo platform. The device makes a connection, which in the first instance is handled by a switchboard process. The switchboard’s sole responsibility is to accept incoming connections, bring to life an operator process and hand the connection over. The operator lives only for the duration of the connection with responsibility for transitioning through the communications protocol, finding the digital device and pushing data samples to it. The digital device caches the data samples and periodically flushes them to an underlying timeseries database.

This design has fault tolerance baked in. If the switchboard process fails, it is immediately restarted, and all that could be lost is a single incoming connection. If an operator process fails, only one communication session is lost, where the unfortunate physical device can try again on it’s next connection attempt (scheduled or ad-hoc). Communication sessions for other physical devices remain unaffected. The digital device involved is also unaffected. This is key as the business value derived from ingesting the sensor data is likely to be based on modelling atop a stable set of digital devices!

Conclusion

Whilst there’s plenty more I could cover, that’s about it for now. Hopefully I’ve conveyed some of the key benefits to using Erlang for IoT platforms, such that you’re encouraged to learn more. If you’d like to do that or take a look the demo platform in action, please reach out to me on mike@crudbetter.com.